Partition of Bengal

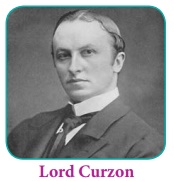

On January 6, 1899, Lord Curzon was appointed the new Governor General and Viceroy of India. This was a time when British unpopularity was increasing due to the impact of recurring famine and the plague. Curzon did little to change the opinion of the educated Indian class. Instead of engaging with the nationalist intelligentsia, he implemented a series of repressive measures. For instance, he reduced the number of elected Indian representatives in the Calcutta Corporation (1899). The University Act of 1904 brought the Calcutta University under the direct control of the government. The Official Secrets Act (1904) was amended to curb the nationalist tone of Indian newspapers. Finally, he ordered partition of Bengal in 1905. The partition led to widespread protest all across India, starting a new phase of the Indian national movement.

Bengal Presidency as an administrative unit was indeed of unmanageable in size; the necessity of partition was being discussed since the 1860s. The scheme of partition was revived in March 1890. In Assam, when Curzon went on a tour, he was requested by the European planters to make a maritime outlet closer to Calcutta to reduce their dependence on the Assam– Bengal railways. Following this, in December 1903, Curzon drew up a scheme in his Minutes on Territorial Redistribution of India, which was later modified and published as the Risely Papers. The report gave two reasons in support of partition: Relief of Bengal and the improvement of Assam. The report, however, concealed information on how the plan was originally devised for the convenience of British officials and the European businessmen.

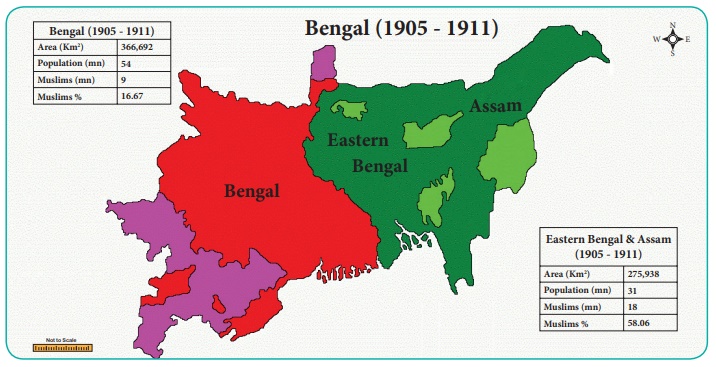

From December 1903 and 1905 this initial idea of transferring or reshuffling some areas from Bengal was changed to a full-fledged plan of partition. The Bengal was to be divided into two provinces. The new Eastern Bengal and Assam were to include the divisions of Chittagong, Dhaka, parts of Rajshahi hills of Tippera, Assam province and Malda.

Aimed at Hindu Muslim Divide

The intention of Curzon was to suppress the political activities against the British rule in Bengal and to create a Hindu–Muslim divide. The government intentionally ignored alternative proposals presented by the civil servants, particularly the idea of dividing Bengal on linguistic basis. Curzon rejected this proposal as this would further consolidate the position of the Bengali politicians. Curzon was adamant as he wanted to create a clearly segregated Hindu and Muslim population in the divided Bengal. Curzon, like many before him, knew very well that there was a clear geographical divide along the river Bhagirathi: eastern Bengal dominated by the Muslims, and western Bengal dominated by the Hindus and in the central Bengal and the two communities balancing out each other. There was a conscious attempt on the part of British administration to woo the Muslim population in Bengal. In his speech at Dhaka, in Februry 1904, Curzon assured the Muslims that in the new province of East Bengal, Muslims would enjoy a unity, which they had never enjoyed since the days of old Muslim rule.

The partition, instead of dividing the Bengali people along the religious line, united them. Perhaps the British administration had underestimated the growing feeling of Bengali identity among the people, which cut across caste, class, religion and regional barriers.By the end of the nineteenth century, a strong sense of Bengali unity had developed among large sections in the society. Bengali language had acquired literary status with Rabindranath Tagore as the central figure. The growth of regional language newspapers played a role in building the narrative of solidarity. Similarly, recurring famines, unemployment, and a slump in the economic growth generated an anti-colonial feeling.

Anti-Partition Movement

Both the militants and the moderates were critical of the partition of Bengal ever since it was announced in December 1903. But the anti-partition response by leaders like Surendranath Banerjee, K.K. Mitra, and Prithwishchandra Ray remained restricted to prayers and petitions. The objective was limited to influencing public opinion in England against the partition. However, despite this widespread resentment, partition of Bengal was officially declared on 19 July 1905.

With the failure to stop the partition of Bengal and the pressure exerted by the radical leaders like Bipin Chandra Pal, Aswini Kumar Dutta, and Aurobindo Ghose, the moderate leaders were forced to rethink their strategy, and look for new techniques of protest. Boycott of British goods was one such method, which after much debate was accepted by the moderate leadership of the Indian National Congress. So, for the first time, the moderates went beyond their conventional political methods. It was decided, at a meeting in Calcutta on 17 July 1905, to extend the protest to the masses. In the same meeting, Surendranath Banerjee gave a call for the boycott of British goods and institutions. On 7 August, at another meeting at the Calcutta Town Hall, a formal proclamation of Swadeshi Movement was made.

However, the agenda of Swadeshi movement was still restricted to securing an annulment of the partition and the moderates were very much against utilizing the campaign to start a full-scale passive resistance. The militant nationalists, on the other hand, were in favour of extending the movement to other provinces too and to launch a full-fledged mass struggle.

Spread of the Movement

Besides the organized efforts of the leaders, there were spontaneous reactions against the partition of Bengal. Students, in particular, came out in large numbers. Reacting to the increased role of the students in the anti-partition agitation, British officials threatened to withdraw the scholarships and grants to those who participated in programmes of direct action. In response to this, a call was given to boycott official educational institutions and it was decided that efforts were to be made to open national schools. Thousands of public meetings were organized in towns and villages across Bengal. Religious festivals such as the Durga Pujas were utilized to invoke the idea of boycott. The day Bengal was officially partitioned – 16 Oct 1905 – was declared as a day of mourning. Thousands of people took bath in the Ganga and marched on the streets of Calcutta singing Bande Mataram.