Linguistic Reorganization of States

An important aspect of the making of independent India was the reorganisation of states on linguistic basis. The colonial rulers had rendered the sub-continent into administrative units, dividing the land by way of Presidencies or Provinces without taking into account the language and its impact on culture on a region. Independence and the idea of a constitutional democracy meant that the people were sovereign and that India was a multi-cultural nation where federal principles were to be adopted in a holistic sense and not just as an administrative strategy.

The linguistic reorganization of states was raised and argued out in Constituent Assembly between 1947 and 1949. The assembly however decided to hold it in abeyance for a while. This was on the grounds that the task was huge and could create problems in the aftermath of the partition and the accompanying violence.

After the Constitution came into force it began to be implemented in stages, beginning with the formation of a composite Andhra Pradesh in 1956. It culminated in the trifurcation of Punjab to constitute a Punjabi-speaking state of Punjab and carving out Haryana and Himachal Pradesh from the existing state of Punjab in 1966.

The idea of linguistic reorganisation of states was integral to the national movement, at least since 1920. The Indian National Congress, at its Nagpur session (1920), recorded that the national identity will have to be necessarily achieved through linguistic identity and resolved to set up the Provincial Congress Committees on a linguistic basis. It took concrete expression in the Nehru Committee Report of 1928. Section 86 of the Nehru Report read: “The redistribution of provinces should take place on a linguistic basis on the demand of the majority of the population of the area concerned, subject to financial and administrative considerations.”

This idea was expressed, in categorical terms, in the manifesto of the Indian National Congress for the elections to the Central and Provincial Legislative Assemblies in 1945. The manifesto made a clear reference to the reorganisation of the provinces: “… it (the Congress) has also stood for the freedom of each group and territorial area within the nation to develop its own life and culture within the larger framework, and it has stated that for this purpose such territorial areas or provinces should be constituted as far as possible, on a linguistic and cultural basis…”

On August 31, 1946, only a month after the elections to the Constituent Assembly, Pattabhi Sitaramayya raised the demand for an Andhra Province: “The whole problem” he wrote, “must be taken up as the first and foremost problem to be solved by the Constituent Assembly”. He also presided over a conference, on December 8, 1946, that passed a resolution demanding that the Constituent Assembly accept the principle for linguistic reorganisation of States. The Government of India in a communique stated that Andhra could be mentioned as a separate unit in the new Constitution as was done in case of the Sind and Orissa under the Government of India Act, 1935.

The Drafting Committee of the Constituent Assembly, however, found such a mention of Andhra was not possible until the geographical schedule of the province was outlined. Hence, on June 17, 1948, Chairman Rajendra Prasad set up a 3-member commission, called The Linguistic Provinces Commission with a specific brief to examine and report on the formation of new provinces of Andhra, Kerala, Karnataka and Maharashtra. Its report, submitted on December 10, 1948, listed out reasons against the idea of linguistic reorganisation in the given context. It dealt with each of the four proposed States – Andhra, Karnataka, Kerala and Maharashtra – and concluded against such an idea.

However, the demand for linguistic reorganisation of states did not stop. The issue gained centre-stage with Pattabhi Sitaramayya’s election as the Congress President at the Jaipur session. A resolution there led to the constitution of a committee with Sardar Vallabhai Patel, Pattabhi Sitaramayya and Jawaharlal Nehru (also called the JVP committee).

The JVP committee submitted its report on April 1, 1949. It too held that the demand for linguistic states, in the given context, as “narrow provincialism’’ and that it could become a menace’’ to the development of the country. The JVP committee also held out that “while language is a binding force, it is also a separating one’’. However, it stressed that it was possible that “when conditions are more static and the state of peoples’ minds calmer, the adjustment of these boundaries or the creation of new provinces can be undertaken with relative ease and with advantage to all concerned.’’

The committee said in conclusion that it was not the right time to embark upon the idea of linguistic reorganisation of States. In other words, the consensus was that the linguistic reorganisation of states be postponed. There was provision for re-working the boundaries between states and also for the formation of new states from parts of existing states. The makers of the Constitution did not qualify the reorganisation of the States as only on linguistic basis but left it open as long as there was agreement on such reorganisation.

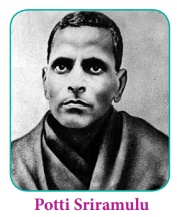

The idea of linguistic states revived soon after the first general elections were over. Potti Sriramulu’s fast demanding a separate state of Andhra, beginning October 19, 1952 and his death thereafter on December 15, 1952.

Article 3, reads as follows:

Parliament may by law- (a) form a new State by separation of territory from any State or by uniting two of more States or parts of States by uniting any territory to a part of any State; (b) increase the area of any State; (c) diminish the area of any State; (d) alter the boundaries of any State;

This led to the constitution of the States Reorganisation Commission, with Fazli Ali as Chairperson, and K.M. Panikkar and H.N. Kunzru as members. The Commission submitted its report in October 1955. The Commission recommended the following States to constitute the Indian Union: Madras, Kerala, Karnataka, Hyderabad, Andhra, Bombay, Vidharbha, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Punjab, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, West Bengal, Assam, Orissa and Jammu & Kashmir. In other words, the Commission’s recommendations were a compromise between administrative convenience and linguistic concerns.

The Nehru regime, however, was, by then, committed to the principle of linguistic reorganization of the States and thus went ahead implementing the States Reorganisation Act, 1956. Andhra Pradesh, including the Hyderabad State came into existence. Kerala, including the Travancore-Cochin State and the Malabar district of Madras, came into existence. Karnataka came into being including the Mysore State and also parts of Bombay and Madras States. In all these cases, the core principle was linguistic identity.

In May 1960 Gujarat was created from Maharastra to fulfil the demand of the Gujarati speaking people. Subsequently, the demand for a Punjabi subha continued to be described by the establishment as separatist until 1966. The trifurcation of Punjab, brought to an end the process that was initiated by the Indian National Congress, in 1920, to put language as the basis for the reorganization of the provinces.